Peace Watch » Kashmir-Talk » My Memoir: My Uncle

My Memoir: My Uncle

A

My Memoir: My Uncle Part II

Z.G. Muhammad

“Words could never tell the joy an uncle brings; an uncle is a bond of faith that even time can’t sever, a gift to last all of our lives.” I don’t know who has said it. Whosoever has said it, whether a big name in literature or an anonymous fellow, but he has said it pretty well? Sometimes, writings by anonymous writers are as rich in content as Shakespearean or Dickensian quotes. At the cost of monotony, let many say he was what we in Urdu call Kaus-e-Qaza- rungoon ki dhanak- a blend of pleasing colours- with multiple shades. He followed a golden principle about life, ‘live your life to the fullest,’ yet was mystic- yes, a mystic to the kernel. Perhaps, I knew more about my uncle than my father- as I wrote in the chapter on my father, in the most tender phase and formative stage, my father was posted outside Srinagar, and for us children, he was Santa Claus who, on weekends brought us toys. Like a shadow, I followed him almost everywhere; he would go and, on many an occasion, accompanied him on weekend boat trips to the Dal Lake- usually a two-night sojourn- of all the places as a young child, I loved to cling him to his in-law’s house.

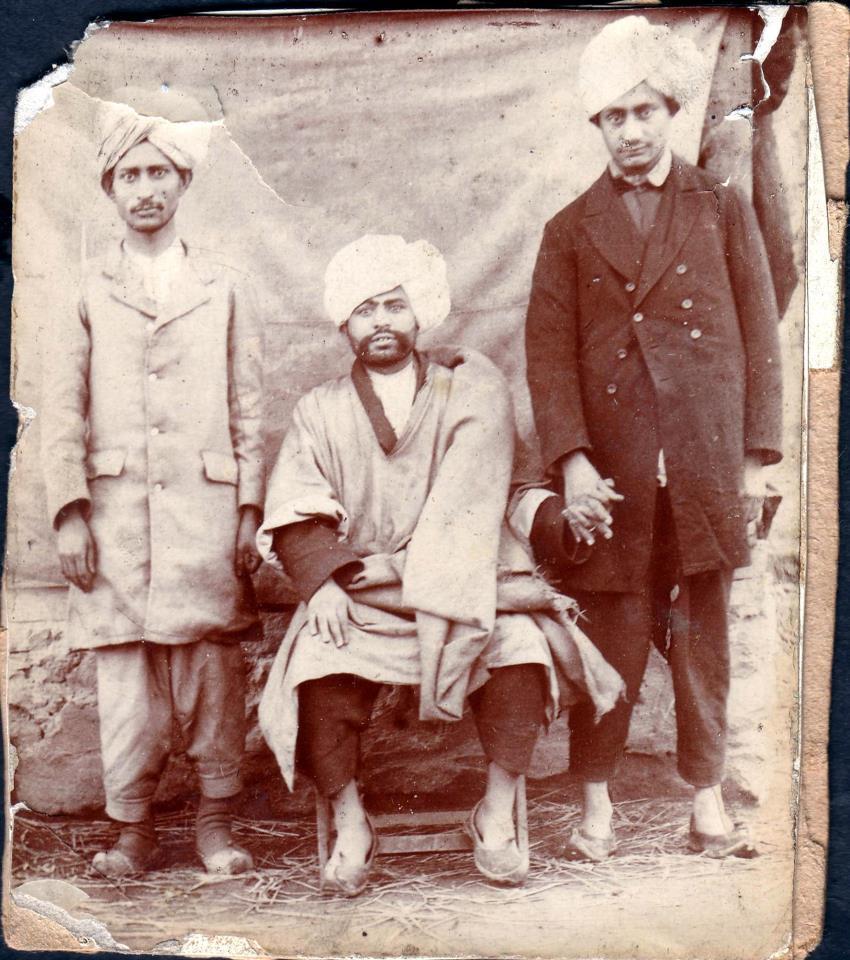

I don’t know the day, date and time of my uncle’s birth. By all stretch of the imagination, we were natives. We had bid adieu to our forefather’s faith, paganism, Buddhism and Hinduism, along with teeming thousands and came under the canopy of Islam somewhere in the fourteenth century. And having said farewell to our ancestors’ totems, taboos and customs, the practice of getting a Zatuk prepared by a Gour (Brahman) had also been dropped, so there was no record of the uncle’s date of birth. The only testimony about his date of birth was his matriculation certificate from Punjab University and the State Subject. He died on December 15, 1979, corresponding to Muharram, 25, 1400 Hijri at 56, one year after his superannuation- then Government employees retired at the age of fifty-five. That suggests he was born somewhere in 1923, in the house where my father, my all-elder brother and I were born. The three-story garden-roof house of five by six inch, slim as a butter slice red burnt-clay bricks, known as Badshah bricks, with lattices window had been constructed by our grandfather at the start of the twentieth century. In the early 1950s, our house had lost its classic look and had been given pseudo-modern grandeur. The garden roof was replaced with corrugated-galvanized iron sheets, the mosaic of Badshahi bricks was sacrificed at the altar of cement concrete and plaster, and the lattice windows having their romance, were killed to be replaced by glass-window panes. I was the last child born under the garden roof that would be rash with Gulal in the spring- and a great feast to eyes till Chinar leaves turned rusty. Unlike my father, my elder brother Muhammad Yusuf and me, my uncle was not an alumnus of Islamia High School. He received schooling at Government High School, Bagh-Dilawar Khan, then known as the State School.

It was on the family grapevine, and my grandmother often mentioned that he was born the same year my elder brother came to the world- my brother was born on September 21, 1946. My uncle was married in a Mohalla at the foothills of Koh-i-Miran, which Kashmiri Hindus call Hari Parbat. The Mohalla, en route to the Astana of the second most revered native saint of Kashmir, Hazarat Sultan Sheikh Hamza Makhdoomi and the highly respected Hindu temple dedicated to Jagdamba Sharika Bhagwati, was fifteen minutes walk from our home. For centuries, in the wee morning hours, before the sun rays glistened, the golden spires of the mausoleums of a score of saints dominating the city skyline; the devotees would tread- some barefoot, some wearing wooden sandals the small road leading to the hillock. Scores of multiple-story houses, of course, more than three-story houses on both the sides of the street and interiors of the Mohalla distinctly suggest that the locality has been one of the prosperous localities of the city. Many families in the locality were engaged in Numdha Making- the thick woollen felt embroidered with floral designs in multi-coloured woollen threads. Many families from the time of Akbar’s invasion have been in the trade. Many other families were also attracted to manufacturing these beautiful woollen rugs after it attracted the western clientele, and its exports shot up, which reached all-time him during World War II. Shipments after shipment of Numadahs from Kashmir started sailing from Karachi port, then the nearest sea port to Srinagar to Europe. The positive spillover effects of the earnings from the exports were seen all over the market. The construction work in the locality picked up, and many elegant four- to five-story-high mansions with grand balconies and intricate panjarakari started dominating the skyline. Having lost the luster, many of these castles and elegant houses still survive in a few Mohalla at the foothill of Koh-i-Maran.

My uncle’s in-laws had been running a local grocer’s shop in the locality for over half a century. Besides groceries, they also specialized in selling faith-related items. Most of the faith-related things they sold were connected with the Pujas of Kashmiri Pandits. The latter walked from distant localities of the city to the two temples, one adjacent to the finely chiselled limestone stairs leading to the Astana of Makdoom Sahib and another in the lap of the iconic hillock. Besides earthen lamps, Dhoop, and incense sticks, they sold sugar crystals Qand and Quinze. Outside their shop, there used to be a long wooden table on which were kept replicas of eyes, legs, and arms, knees perhaps made from German silver or some other alloy – but we believed these were made from silver. Those suffering from connected disabilities purchased them and made them as offerings at the Astana of Makdoom Sahib, with prayers for speedy recoveries from the disabilities. On its face, it seemed a pagan practice, but how old the tradition was and who had perpetuated it, I never bothered to look into it; even as a child, I was not attracted by these clumsily made replicas. One thing I liked most in the shop was Qanad- a lump of sugar looking like a Kulafi, and I eagerly waited for Razak Kak, owner of the shop, to give me one.

The Qanad was an incentive; some other attractions made me remain towed to my uncle whenever he went to his in-law’s house. In their compound, they had a huge pond with a tuft of sparkling duckweeds looking from an edge; it looked like the turf of a mini-cricket stadium. And a gaggle of geese and flocks of ducks swam across it, and watching them was a lovely time pass. But, what scared me the most were the white swans; once they came out of the pond, they chased me away and often made me cry for help. I admired the plumage of the ducks’. Their golden and deep, iridescent feathers form a ring around their neck, making them excitingly graceful. Many times, I ran after them. The distinctive curl of a male mallard’s had an attraction for me. I was perhaps too young then to catch the mallards and pull out the curled tail feather that we called “woonk”.Later on, during our student days, a couple of my friends, for curling their hair on the forehead in Sadat Hussain Mantoo’s style, were nicknamed Woonkal. A girl senior to us in the University had also earned this dubious distinction; perhaps she was a student of the Urdu Department.

The swallows excited me much more than these aquatic birds; the swallows and their nests had enormous excitement and attraction for me. Theirs was a joint family of four brothers; perhaps then, there was no concept of nuclear families, and separating from the central family was counted as the decadence of the society. Having also benefitted from the new fortune that had come to the locality after exports of the woollen floorings had picked up, they added one more majestic to their exciting houses. The top floor of one of their house had become a haven for the swallows. In early spring, when these migratory birds made their presence felt by making graceful flights across the roads, they opened all the ornate windows of the Kani (hall) top floor to enable these birds to make their nests. The dozens of swallows like artisans making their nests on the roof beams were worth seeing. In the Kani, the best choice for the swallows to make their nest was the king post ‘Nari-Kot’. I loved watching the swallows dipping dextrously a straw or a twig in a muddy puddle and like a craftsman artistically weaving a nest underneath a ‘Dub’ – cantilevered wooden balcony or on the wooden trusses of the top floor.

The bird-making nests inside the houses boded well for my uncle’s in-laws. It was accepted as a harbinger of good fortune. That was true about all the families that opened windows of their houses for swallows making nests. Parents warned Children against damaging the nest, spoiling the eggs and harming the chicks. Despite producing many different songs and musical twittering, the bird carrying a mystical aura around it was not put into a cage like many other songbirds. Our admiration for the swiftness of the bird with a forked tail was more than we had for any bird, but we never aimed our catapult at it as we did for a sparrow or a crow. For swallow-watching, my uncle’s in-laws remained my attraction even during my middle school days.

(To be continued)

Comments are welcome at zahidgm@gmail.com

Filed under: Kashmir-Talk