Peace Watch » Kashmir-Talk » My Memoir My Father: He Died In Harness Part VIII

My Memoir My Father: He Died In Harness Part VIII

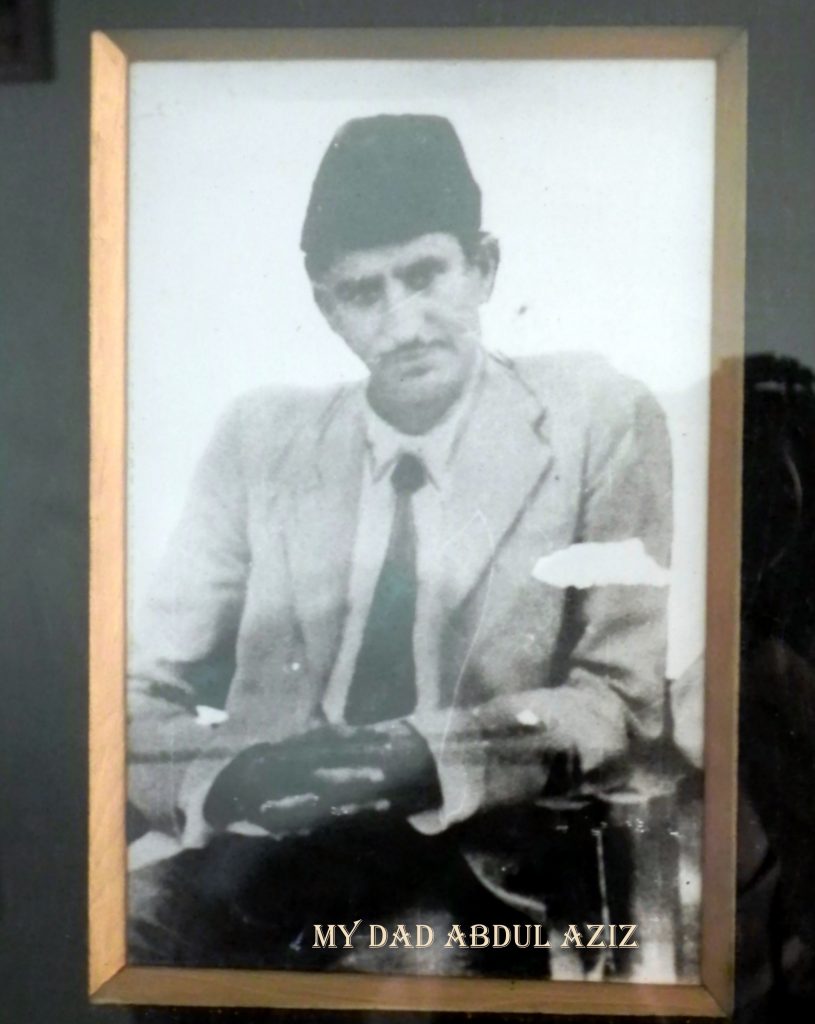

He Died In Harness: My Memoir My Father

ZGM

These were the days of ecstasy unbounded for my friends and me- we were going to have an extended recess, a grand leisure time full of thrill and excitement. We had just appeared for the board examinations for class eight, and it was to be a long post-examination break- no school and no tuition till results would be out. Suddenly, in my case, the sweetness of the holidays turned bitter when I learnt that my father intended to put me in a different school in the uptown in class nine- it would be as good as uprooting me, I would lose all my friends and playmates.Sending children to Christen Missionary School (CMS) Tyndale Biscoe School, Sheikh Bagh those days was “aristocratic” and elitist. It was reputed as one of the best schools for bagging many positions of the matriculation examinations; nonetheless, my alma mater Islamia High School was not far behind it in bagging the first three positions. There was no honours board in our school; had there been one, the number of illustrious school alumni would have run in hundreds. One could hardly imagine anyone top in the Muslim society of Kashmir who had not been a student of my school. In the morning, beelines of boys from all directions could be seen entering through various gates into the school as against those going to Sheikh Bagh School from our locality be counted on fingertips. They belonged to affluent families with business outlets on the Bund or the Residency Road and some government officers. My elder brother Yusuf too, was a student at the CMS school. In the morning, when I wore my school uniform, Khaki trousers, a sky-blue poplin shirt, and he dressed in grey knickers and a white shirt, Ilooked sartorially elegant than him. Perfectionist to the core that my brother was during his student days, his bike equipped to the full with a basket, a carrier, a dynamo, two bells, multi-coloured axil brushes looked like a bride.

Like many boys in the Mohalla, I was also envious of his Sen-Raleigh bicycle; very few could afford it-it mainly was exported from India. Father had gifted it to him on his passing class VIII examination- it was popularly known as the middle examination. The prestige of the middle pass had enhanced after Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad had become Prime Minister. He was believed to be a middle pass but had outmanoeuvred and elbowed out an MSc from AMU. When we joined college, he ceased to be the Prime Minister but continued to be chairman of our college. Once, on his visit to our college, he entered our classroom and spoke fluently in flawless English, taking us by surprise. When he left the class, guessing started about his English language learning. One boy said that his father had told him that after passing the middle examinations, he was appointed as a teacher in Leh, where he had become David Bakshi- and there he had mastered the language. Someone else said Prof. S.N. Thusu, principal of our college, in his days as a teacher of English literature in SP College had taught him the language. We all agreed that Thusu Sahib might have trained him in the language. Professor, Thusu had a great dress sense; he draped simple but significant, he often wore elegant pinstripe suits and a beautifully tied light green turban. Despite heading the college, he took English classes- and with flawless pronunciation left us spellbound.

Coming back to my brother’s bicycle, for the adornments he had put on it, it attracted the attention of all passers-by. He, in reality, had made a dandy of his bicycle. In the 1960s, our schools days, bicycles were seen as one of the most precious gifts rich gifted to their sons-in-law as dowry. Learning biking was a tedious process; we knew in three stages – many times returning home with bruises. Girls then rarely learnt cycling. I remember seeing three women using the bicycle; one was a christen nurse working in a missionary hospital. She was nicknamed Kala Miss. The second was the daughter of a Maharaja Hari Singh time bureaucrat and the third a girl student of medical college having relations in our neighbourhood.

Most grown-up children dreamt of buying a bicycle on passing their matriculation examination and peddling the same to the college. But just a few could afford it. Owning a bike also haunted many government employees who could not afford it. Then the pay scale of a senior clerk used to be Rs. 60-5-100 and the bicycle cost ranged from Rupees two hundred to three and fifty; there were a couple of brands and models, Star was the cheapest, and Sen Raleigh manufactured in Asansol and Kanpur was an expensive one; it cost three hundred and fifty rupees. There were a few bicycle shops in our locality; they were all repairing shops, and none of them sold new bicycles. Some shops sold second-hand bikes, and few others kept a dozen or so for hire. The minimum rental was two annas for an hour and one or two rupees for the day, depending upon its condition. Those who hired for a fortnight would get a concession.

Most of the shops selling new bicycles were in uptown markets; the owners of the two in the Palladium Lane lived in a neighbouring Mohalla on the way to our school. I had not to wait for passing the matriculation examinations for having a bicycle. If I scored well in the Class VIII examinations, I would also get a bike like my elder brother; my father had promised a high-quality bicycle. My elder brother had left the gates of the CMS. Tyndale Bisco school and was pursuing F. Sc in Sri Pratap College – a college that also had a tale to tell about the struggle of Kashmiri Muslims for getting higher educations. The portals of college were latched for a generation ahead of my father. And it had taken a battle royale for them to see the doors of the college open to them- my father often mentioned the struggle put by the first pass outs from my alma mater. They made the Viceroy of India appoint a committee under Mr Sharp to look into Muslims’ grievances. That was history; its gates were opened to all, and it lived up to its motto ‘AD AETHERA TENDENS’ (fly high and higher).

On passing the board examination, my father had decided to get me admitted for class nine in Bisco School; he wanted me to give my matriculation from the missionary school. I was hostile to the idea; I had many friends in Islamia High School- most of them without pretensions of coming from the elite and neo-rich family, full of vigour and vibrance. I nursed an acrimonious feeling against my father, who wanted to shake my roots and push me into an alien atmosphere. But there was an incentive attached to shifting to the new school; I would get a bicycle after the results were announced. The very idea of pedalling to school everyday morning had an incredible thrill and excitement for me. Ultimately, the D-day arrived, the results were out, and I had done well- not to the expectation of my uncle, who expected more from me, but my father had no complaint. My father’s only advice was to work hard and doing well in matriculation examinations. He emphasised that the class ten certificate for life becomes the testimony of efficiency; it is shown from the first appointment to retirement on many occasions. Wearing a smile on his face surprised me that he had ordered an English Raleigh bicycle with Noor Cycle Works at Regal Chowk.

I had learned cycling the hard way – by making mistakes, getting bruised, and sometimes somersaults hurting to bleeding my knees and legs. I had a good time- quite a good time at Noor’s shop watching the assembling of my bicycle. I wished to paddle the bike home, but Noor was afraid if I was a capable cyclist. To impress me that I should drive it home carefully, he repeatedly quoted its price; it costs Rs. 550 – it is big money. I was as excited as I would be as a kid at the Badamawari festival, buying gas balloons, letting them go in the air, and gazing at them till they became a dot in the sky.

Cycling from the Residency Road to home on my new bicycle was a dream come true- it was a long-cherished toddler’s dream that had come true. As a toddler, my big goal was to have a tricycle. A small cycle workshop was in the corner of a makeshift market at a three-minute walk from our house at Nowhatta roundabout. One Muhammad Abdullah, our neighbour, popularly known as Abal Khar, owned it. He was a fabled man for my sibling and me; he had been ex-servicemen who in World-II had fought along with British soldiers in some country- and he missed the chance to get married. He was perhaps the only person in our locality who had joined the army- and fought in some alien deserts. There were no new bicycles in his shop. He was selling old repaired bikes. In the corner of his shop, there was an old kid’s tricycle- its wheels had rusted, and the leather seat was worn out. He had perhaps purchased it and many other old bicycles some years back in an auction outside the Residency immediately after the British departure and flight of the last monarch from the valley. My dream was to have this old tricycle perhaps used by some English child for years. It often attracted me like daffodils draw spring butterflies. I often stopped at his shop and implored him to give this tricycle to me. One day I took my uncle with me; he negotiated some price. Abal Khar promised to keep the tricycle ready after repairs in a week but never kept his promise till I learnt half-peddling bicycle. Tired of visiting Abal Khar, I had dropped the idea of having a tricycle long before and dreamt of having a new bike- the English Raleigh bicycle was the best thing patience could have bought me.

I had not put as many adornments on my bicycle as my brother had; still, it was not as austere as that of my uncle, that had just one bell and a dynamo. I whizzed on my way to school through Munawara Abad Road, which used to be one of the beautiful trafficless serene willow tree avenues with water channels on both sides’ rash with water lilies- white and purple. And roadsides laced with tufts of buttercup flowers. It now became routine for me before my brother left for college. Feeling at the top of the world in my wildest dreams, I had not imagined that the Raleigh bicycle would be the last gift from my father, and the darkest clouds that were to shadow my siblings and me for many decades were over hovering on my head.

Our father was meticulous to a fault, to use Dickins phrases’ punctuality, order, diligence and determination to the extent of workaholic were his intrinsic traits. When on a job, which he was even on the off-days, he was free and easy about food; it was a regular complaint against him that he is not bothered about health. But, if he had any health issues, we children did not know- we mostly met our father at dinner time when he made it home earlier, and his health was never discussed at dinner. One fine morning we learnt that father had got some X-rays done at Dr Shivaji’s clinic – and on seeing these X-rays, Dr Ali Jan had informed our uncle about the graveness of father’s ailment to my uncle. He advised surgery. I wouldn’t know with surety if Dr Jan suggested the name of Dr Santokh Singh Anand, then a top name in surgery, Professor and Head of the Department of Medical College, Amritsar, Punjab. That father had some life-threatening ailment, except my uncle none knew about it, my grandmother-innocence incarnate did not know it, my mother was as ignorant as children. Bells about the seriousness of the father’s ailment started ringing in the family once it was announced that the father, accompanied by our uncle and two of his nephews, would be travelling to Amritsar for surgery- from Srinagar, they will take a flight to Jammu. From Jammu, they would hire a taxi to Amritsar. We were taking our father’s ailment in a stride in our innocence. On his departure, once we saw his colleagues Tika Lal, Badari Nath Mattoo, Shamboo Nath, Manohar Lal, Radha Krishan, and some relatives gathered at our home brooding- downcast bidding him adieu, we realised there was something grave about his ailment.

Those were almost incommunicado days; the only telegram we had received after his departure was about their safe arrival in Amritsar. And whatever communication our uncle had about our father’s health was with one of his nephews, Mama Mir- in their absence, he was looking after our home. One evening Mama Mir shared news about the surgery of our father- generally, children were kept out of the loop about information received from Amritsar. Now, we expected returning to home any day, hale and hearty.

On an evening about a week after father’s surgery, we had just finished our meals, two older women, our neighbours entered into our kitchen. They tried to console our mother, and a few of our neighbours followed the ladies. The neighbours put some mats in our compound. And they announced that our father had passed away, and his body from Amritsar was in a van outside. Six people had accompanied our father’s body from Amritsar, our uncle, his two nephews and three of our neighbours, Mohammad Amin, Mohammad Maqbool and Ghulam Mohi-U-Din. Our three neighbours ran a small leather Jacket manufacturing factory in Hall Bazar, Amritsar. On hearing about the death of our father, they closed their factory and accompanied the body.

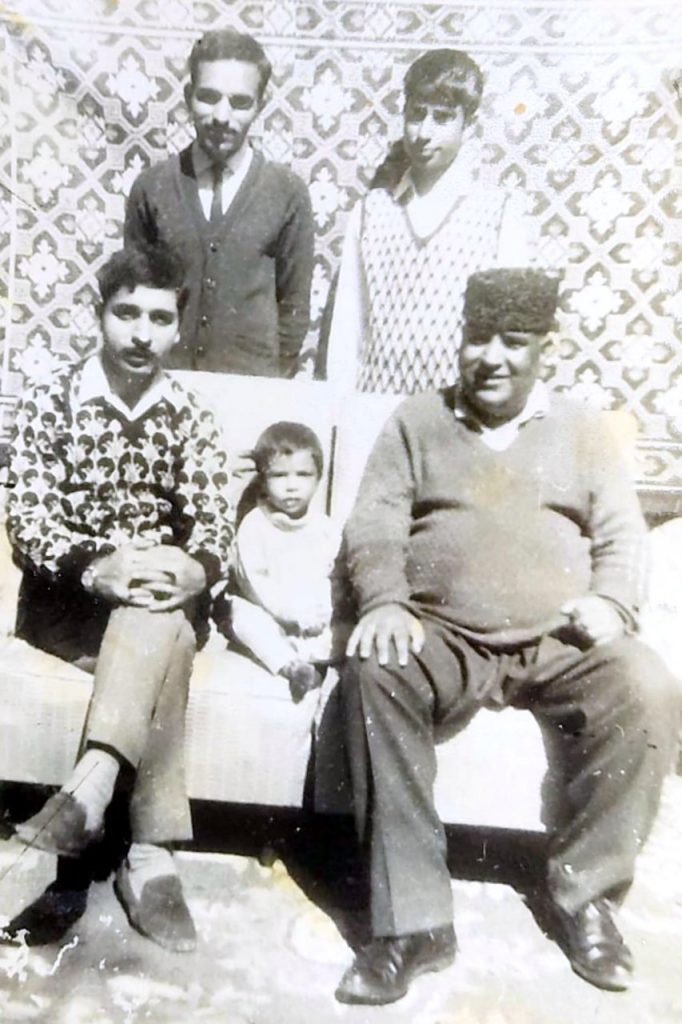

In the death of our father, our whole world changed…. He was 39, Yusuf’s eldest of us was 16 and our youngest sister was two years old.

Filed under: Kashmir-Talk