Peace Watch » Editor's Take » In Stifling Atmosphere Forget History! Create Literature

In Stifling Atmosphere Forget History! Create Literature

PUNCHLINE

Forget History! Write Literature

By

Z.G. Muhammad

A fortnight back, a single column news item in newspapers announced the death of Mushirul Hasan, an Indian historian and former Vice Chancellor of Jamia Millia Islamia and author of a dozen and half books. His forte has been Islam in South Asia, communalism and birth of India and Pakistan as independent dominions. Except for some occasional remarks in sync with the ‘hegemonic discourse’, he had no direct connection with Kashmir. Moreover, he was no exception to the overwhelming Muslim intellectuals in India, who see Kashmir as toxic ‘white snakeroot plant’, – better to be avoided. His only connection with Kashmir has been through his father historian Mohibbul Hassan, who has added a classic work ‘Kashmir Under Sultans’ to the medieval history of the land- “the zenith of civilisation that had made Kashmir as the envy of the world.”

The death of a historian or writer often reminds about the works one has read by the author. Many times, it is the obituary of the dead author that attracts a reader. Somehow, I never felt reading Mushirul Hasan. Nonetheless, it was a two-volume book, ‘India Partitioned- The Other Face of Freedom’ beautifully brought out by Lotus Roli edited by him that often attracts me and makes me fillip through its pages. It is not a book on history, but a work of literature that narrates the holistic story with all the subtleties that history fails to do – and perhaps cannot do. The book is a rich anthology of translated works of celebrated Urdu short story writers and poets, which reigned supreme on the literary scene of the Subcontinent during India’s Struggle for freedom, at the time of birth of India and Pakistan as independent counties. There is hardly a name from Mumtaz Mufti to Rajinder Singh Bedi to Ismat Chughtai to Saadat Hassan Manto of those times in Urdu fiction; whose translated works are not included in the collection.

Likewise, the volumes contain translations of poetry from Makhdoom Mohiuddin to Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Urdu prose writings of famous writers like by Agha Shorish Kashmiri and interviews with giants of literature. Despite, Hasan for the compilation having chosen writers subscribing to the left ideology and selected works from a particular point of view, yet the literature has its way of telling the holistic story, with the minutiae that history can hardly say. In his introduction to the compilation, the author quotes an extract from Rahi Masoom Reza’ novel Aadha Gaon (Half Village) to tell us how Reza had vividly described the dominant strain of the League politics in his village. Although the novel was written from a particular standpoint, the quoted paragraph with all refinement explains, what was passing through the minds of the people of the village, caught at the crossroads of the two diverse ideologies- history would rarely narrate it with that ability.

The history would never record, the mental trauma that an individual suffered the way a writer like Manto looked at the  happenings after the British left the sub-continent:

happenings after the British left the sub-continent:

“Everyone seemed to regress. Only death and carnage seemed to be proceeding ahead. A terrible chapter of blood and tears was being added to history, a chapter without precedent. India was free. Pakistan was free from the moment of birth, but in both states man’s enslavement continued: by prejudice, by religious fanaticism, by savagery.”

Even when one looks at our literature that was written not from any specific standpoint, it showcases our narrative with its nuances and finesse that is beyond the realm of the history. And a single verse can tell a whole a story and leave an indelible imprint. No work on history tells us about the metamorphosis that the society was undergoing in the fourteenth century and how the hegemonic caste system was melting down as candidly as verses of Lal Ded do:

“I renounced fraud, untruth, and deceit,

I taught my mind to see the one in all my fellow-men,

How could I then discriminate between man and man,

And not accept the food offered to me by brother man.”

“The thoughtless read the holy books

As parrots, in their cage, recite Ram Ram

Their reading is like churning water,

The fruitless effort, ridiculous conceit.”

That literature tells stories of the nations more powerfully than history, in our case, it is more evident in the poetry of Iqbal. He summed up the cruellest joke in the human history of selling a nation as merchandise that the British had played with us in one verse so robustly that it echoed in every home in the region.

“Dehqaan-o-kisto-joay –o-khayabban faroakhtand

Qaume faroakhtand-o-chi arzaan faroaktand”

(Their fields, their crops, their streams, Even the peasants in the vale,

They sold, they sold all, alas! How cheap was the sale?)

A dozen books on history would not tell the story of our plight to the world outside the ramparts of the Valley as persuasively as this couplet did. Iqbal’s poetry on Kashmir including his Saqi Namah, mobilised masses in British India to rally behind the people of Kashmir and raise their voices against the bigoted rulers who treated millions of humans worst then quadrupeds.

If literature is source material for writing history or not is a debate for historians. But, when history writing suffers expediency, it is the literature that tells the story and says it so eloquently that touches human hearts and perpetuates as the narrative of a nation. In 1947, when historians were caught up in the web of expediencies and strangulation, in this choked atmosphere, it was Ghulam Ahmad Mahjaoor, who through his just one poem ‘Azadi’ captured the terrifying experiences that many dared not to talk about or write. Decades after, the poem continues to be the preamble for the post-feudal- era rule. Chitralekha Zutshi, the author of ‘Language of Belonging- Islam, Regional Identity And Making of History,’has started the introduction of her book, with Mahjoor’s this poem. The poem besides reflecting the disgusting scenario as obtained at the time of its writing, to quote Zutshi, “Mahjoor’s lesser known (I will not call it lesser known) poem, reflects Kashmir’s ongoing engagement with, and deeply ambiguous relationship to the bywords of the postcolonial era- independence, nationalism, citizenship and rights.”

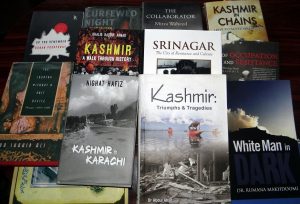

The Literature surpasses history, in as much as many historians pick up verses and sentences from literary works not to embellish the texts but to add to the significance of the chapter. Of late the lines from Agha Shahid Ali, Bashrat Peer and Waheed Mirza have become popular even with some Western historians like Victoria Schofield to start chapters of their books.

History writing can wait, it can wait for better times. Nonetheless, let us create our literature, in the vein of poet Mahmoud Darwish, one, for our purgation and two, for the catharsis of others.

Filed under: Editor's Take · Tags: Arundhati Roy and Kashmir, Freedom Struggle, Kashmir Dispute, Lal Ded, Z.G. Muhamamd