Peace Watch » Editor's Take, Perspectives » Declassify Kashmir: Let people in India Know the Whole Truth

Declassify Kashmir: Let people in India Know the Whole Truth

PUNCHLINE

Declassify Kashmir

By

-

Z. G. Muhammad

Thirty-five years back, like Banquo’s ghost, a couple of questions haunted my mind at regular intervals. Why Sheikh Abdullah, the man Friday of Jawaharlal Nehru who had greeted Indian troops on their landing at Srinagar airport on October 27, 1947, and made the “accession” of the State possible was six years later unceremoniously dismissed as Prime Minister of the State and imprisoned. Moreover, if there was something outside the State narrative: ‘That the United States has encouraged Abdullah to plot for an independent Kashmir- and he had consented to the same. New Delhi had projected his meetings with Democratic leader Adlai Stevenson at Srinagar as glaring evidence about the conspiracy.’

Thirty-five years back, like Banquo’s ghost, a couple of questions haunted my mind at regular intervals. Why Sheikh Abdullah, the man Friday of Jawaharlal Nehru who had greeted Indian troops on their landing at Srinagar airport on October 27, 1947, and made the “accession” of the State possible was six years later unceremoniously dismissed as Prime Minister of the State and imprisoned. Moreover, if there was something outside the State narrative: ‘That the United States has encouraged Abdullah to plot for an independent Kashmir- and he had consented to the same. New Delhi had projected his meetings with Democratic leader Adlai Stevenson at Srinagar as glaring evidence about the conspiracy.’

My urge to find an answer to these questions and to know more facts or stories behind the scene about the dismissal of Abdullah took me to some friends of Jawaharlal Nehru, who in the fifties was in the thick of things about Kashmir including former Prime Minister, Morarji Desai. Nehru, after the deposing of Abdullah on 9 August 1953 had sent a couple of his friends like Khawaja Ahmed Abbas to see Sheikh Abdullah in the Kud Jail for mending his fences with him. Abbas had a soft corner for Abdullah. He did not subscribe to the conspiracy theory but saw Abdullah as a nationalist committed to India and secularism. Nonetheless, Morarji Desai believed that Abdullah was involved in the conspiracy and during his meeting with Stevenson had looked for American support for an independent Kashmir. In a recorded interview, he told me that ‘Jawaharlal had shown him some important papers about the conspiracy and these papers were in the Nehru Museum, New Delhi.

I wrote a couple of letters to Director of the museum. Nonetheless, the letters evoked no response. For seeking access to papers relating dismissal of Abdullah, in the early nineties, I visited the museum couple of times but returned disappointed. Some years back, a Kashmiri born American historian who has so far written two books on Kashmir and is working on third expressed her disappointment about close-mindedness of New Delhi about research on Kashmir told me that every document on Kashmir from 1819 to 1960, is classified and all scholars are denied access to them.

There are indications that this ‘icy-closeminded’ attitude about Kashmir archives has started melting down. A couple of days back the Ministry of Culture, Government of India, started a month-long exhibition of some important documents on Kashmir at New Delhi. The exhibition has been curated by the National Archives of India to tell India’s story about the accession of Jammu and Kashmir to people. The exhibition held to mark seventy years of “accession of Jammu and Kashmir to India” has been titled as “INDIA @ 70: THE JAMMU & KASHMIR SAGA”. It is expected to conclude on February 10.

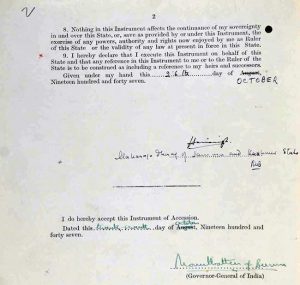

It is perhaps for the first time that New Delhi has allowed people to glean through selected documents on Kashmir. The official handout claims that ‘original letters, telegrams, archival rare documents that include important documents like The Treaty of Lahore, 11 March 1846, The Treaty of Amritsar, 16 March 1846, the Instrument of Accession, 27 October 1947, Standstill Agreement between the newly independent dominions of India and Pakistan and the Princely states of the British India prior to their integration in the new dominion have been put on the display.’ Besides, these documents, which are an integral part of the contemporary Kashmir narrative the government has exhibited some ‘rare vintage photographs, documentaries maps, soldiers’ maps, newspapers reports about Kashmir.’

Most of the ‘treaties’ and ‘agreements’ exhibited have been in the public domain since long and these have been written about, dissected and analyzed by historians, academics, and political commentators. Many historians from Alastair Lamb to Dr. Abdul Ahad have challenged the fact and date of some of the essential documents on which the story of accession hinges.

The one-month exhibition ostensibly is politically motivated in as much telling to people in India about how Nehru had bungled up Kashmir problem and the right-wing politicians like Syama Prasad Mookerjee had clarity on it. There is a section titled ‘Syama Prasad Mookerjee on Jammu & Kashmir issue.’ In this section some letters of Mookerjee to Jawaharlal Nehru and Sheikh Abdullah have been put on display- these do tell a story about the developments in the state in the early 1950s that ultimately resulted in the deposing of Sheikh Abdullah. In fact, one letter of Mookerjee which was partly reproduced by New Delhi newspaper subtly tells how Jan Sangh in the fifties wanted to perpetuate the Maharaja’s rule in Kashmir and see it continues as a Hindu state. “ His letter to Abdullah also exposes the schism between Jan Sangh and National Conference over the rule of J&K shifting hands from the ‘Hindu Dogras’ to the ‘Kashmiri Muslims’.” (TOI 12-1-18). The exhibition might have been nuanced to make a ‘political point’ that the Hindutva leaders played a proactive role in Jammu and Kashmir when the Dispute first arose and use it against first Prime Minister of India and Congress but in the ultimate analysis, it will not only enrich but also strengthens the Kashmir narrative. Even a single letter like that of 27 September 1947 by Jawaharlal Nehru to Sardar Patel which was not included in the Nehru correspondence but founds it way in the published correspondence of Sardar Patel had the potential of deconstructing the much-orchestrated narratives of the National Conference and New Delhi about the happenings in 1947 and the accession.

Such exhibitions, and giving the excess to students and scholars to Kashmir documents in the National Archives of India would be a good beginning. The iron curtain policy about Jammu and Kashmir papers instead of solving any problem has befuddled the public mind in India- thus for fear of vote politics stopped even well-meaning leaders to address the problem in keeping with its history.

India needs a declassification policy to allow the scholars to sift the grain from the chaff- the whole truth needs to be told to the people.

Published in Greater Kashmir on 15-1-2018

Mail your views at zahidgm@gmail.com

Filed under: Editor's Take, Perspectives · Tags: Kashmir Accession, Kashmir Archives, Z. G. muhammad