Peace Watch » Editor's Take, Memeiors » STORY OF MY FATHER

STORY OF MY FATHER

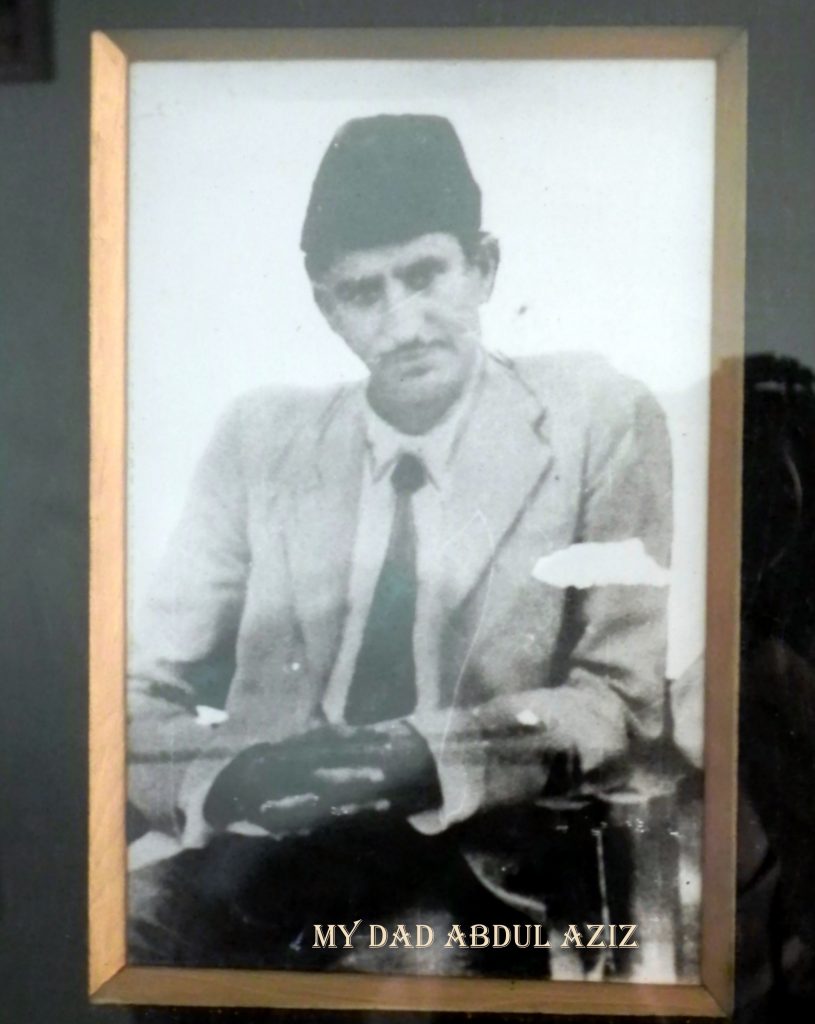

My Father.

I had bid farewell to a multi-coloured Watanigour willow walkermade in Islamabad. I don’t know if a rouht phitrawan (bread breaking) ceremony was arranged on my first step without a walker, as was the tradition.

I had inherited the walker from my elder brother Mohammad Yousf, and it was passed on to my younger sibling Ghulam Hassan. Along with a walnut wood crib, a mace with quartz head, an old lantern, an old gramophone record player, couple of ‘sandal’s, Watanigour was part of the family heirloom that in later years of my childhood had made the loft of our house a place of attraction for me. Before the coloured iron trunk boxes had arrived in the market and had become brides craze for storing vardan, the sandal used to be the most important possession for keeping silver jewellery, shahtoosh, pashmina and ruffle shawls and precious clothes. The sandal used to be deeply carved on the top, and three sides’ rectangular boxes made from deodar wood, with brass or iron strips its corners adding to its strength. One carved boxes blackened with age was stuffed with old story boxes with flashy covers, small booklets on Sufiana Music, and some old Urdu and English novels. As I grew older, I had dug out a couple of novels from one of the boxes- a hive of silverfish. Baroness Orczy historical novel ‘Scarlet Pimpernel’ was one of them. The daring hero of this novel, published in 1905, lived in me for many years. The assortment of books in the ‘Sandal‘ reflected on the floating literary tastes of my father and his younger sibling.

Saying goodbye to Watanigour was not an ordinary thing in my life; it was as good as losing independence. To the claps of my aunt and mother, I could push my walker in any direction without any hassles. My fall even got me cheers and not jeers. Now things were to change; I was on the threshold of following a schedule that would be with me like my shadow for the rest of my life. Unmindful of where I was going, holding hands of my uncle and brother on a fine morning, I entered the gate of a four-story-high blooding with its roof in full blossom, just at five minutes’ walk from our home. With lots of children, hundreds of them strolling and running around, vying each other, the compound was cacophonous as a willow coop with hen and dozens of chickens inside at the daybreak. In my ear, my brother whispered, it is your school; I did not react; perhaps I did not understand its subtleties. In the meantime, someone continually hit a giant gong with a massive mallet, at least for half a minute at the entrance of a one-story building coloured red. Suddenly, there was a semblance of discipline, and all boys gathered in long ques on the side of the compound. My uncle and brother conducted me into a small room in the single-story before a yellow turbaned man with a yellowish-red mark (Tilaka) on his forehead. My uncle presented him with an application on plain paper for my admission in the kindergarten. He was particular if my name and date of birth had been recorded correctly in the register. The turbaned man (later on, I came to know was teacher Kashi Nath) enquired from my uncle why my father had not come along with me to the school on the admission day. ‘He is posted in Baramulla and comes home on weekends and spends Sundays with family,’ my uncle informed him. The two got engaged in a long conversation; most of their discussions went right over my head. But, the parting sentence of my uncle got itched on my mind: Pandit Saib, please see his date of birth is recorded correctly.

On Saturdays, after dusk, my grandmother, mother, everyone in the family, without blinking eyes, gazed at the main gate of our home, waited for our father’s arrival. No moment accompanied by robust a bit squint, dressed in khaki’s, turbaned orderly Amir Khan, he entered the gate, and there was a lot of excitement in the house. It would be the rarest occasion when he would not have got a big rooster, a waterfowl or a dead flying duck with his neck tucked under a wing called Shikar or fish from Sheera, Baramulla with him for the family. Sheeri fish was famed for its variety, size and taste. One evening Amir Khan to the awe and excitement of grandmother and all others, entered into the kitchen with a bigger than usual fish, weighing at least six to seven seers. Simplicity incarnate as my grandmother was, got worried if it would be safe to cook such a giant fish; in her innocence, she took it for examination by a local medical compounder Damodar Nath. Once, he okayed the fish was cooked for lunch for the extended family.

In a sense, Sundays used to be gregarious days for us because they brought our cousins, all nephews and nieces of my father to our home. On seeing them, my grandmother’s face always brightened, and she looked fresher- they were the only legacy of her daughters. She had three daughters elder to my father; the eldest had died of a heart attack, and the younger two were consumed by tuberculosis. She often attributed their suffering tuberculosis to the maltreatment by their in-laws. Instead of calling our father Mam Jan or Mamu Jan, they addressed him as Baijani and all of us, my sibling, including domestic help, called him similarly. He looked after them very well, made them feel very comfortable by taking care of their needs. In my preschool days, I looked upon my father as a visitor who dropped in at our home on Saturdays evenings with a bag full of gifts.

I don’t have even the dimmest idea; if my father ever took me in his lap, hugged me or kissed my rubicund ‘Glaxo baby cheeks at his weekly arrival. No one, not even my mother, ever told me about it, and I also never inquired about it. Nevertheless, I have inherent confidence; he did not consider me inauspicious, as my grandmother did, for me, having tumbled into the world when Kashmir was caught up in a whirlpool of uncertainties- the uncertainties haunt me even seven decades after. Like rice, flour and tea leaves, the sea salt was rationed through political hoodlums on political considerations; my grandmother had a lot more hate for these goons than she had for the soldiers of the Maharaja. Although my mother was severely sick when I was born, still she saw me as a blessed child because famed Majzoob Nabi Mout, nicknamed Bonigoud, had brought new flannel pherans for my elder sibling and me. And he had told my mother that they are “Lassan Liaq” – they are worth a cherished life. As time ticked on, father, on his Saturday visits, ceased to be a weekly visitor to me; now, he was someone very affectionate person who brought gifts. On the day of his departure for Baramulla, I also joined my elder brother, the family’s darling, inputting demands before the father- the list of his requests was always long. From a bird seller Ama Pawa that often was a stopover for me on the way to school, I had known that partridges in his large cages inside his shop were found in Baramulla. One Monday morning, I also added to his laundry of demands and asked for a pair of partridges. It has faded from memory if it was coming weekend or next to next Saturday when I felt at the top of the world on seeing father’s orderly Amir Khan entering our compound with Kaanew Thup, a pretty big cage made of reddish twigs. On seeing a pair of partridge inside, I wanted to jump over Amir Khan and snatch Thup from him and touch the silky feathers of the partridges and feed them.

The pair of partridges was no less than Aladdin’s treasure and orderly Amir Khan, a genie who could get anything for me from Baramulla. Caring for the birds had become a whole-time job; I had gathered sufficient knowledge from Ama Pava, our Mohalla birdshop owner, about feeding them. Songbirds; a variety of them thrushes, wagtails, pipits, golden oriole, tits, doves and parakeet in different types of cages, dome and pyramid-shaped kept me glued to his shop. I wished to have them all and fill our home with their merry songs that Pava told me were their prayers- he also said to me that he caught these birds in and around Dal and Nageen lakes and Badamwari. If these were found in Baramulla, he did not know. Gazing on the Deed (gate) on Saturday evenings and enthusiastically waiting for my father became my pastime also. His very entrance brought warmth and glow to my face- for me, he was not a stranger but someone very intimate. My Memoir: My Father Was Apolitical

The pair of partridges was no less than Aladdin’s treasure and orderly Amir Khan, a genie who could get anything for me from Baramulla. Caring for the birds had become a whole-time job; I had gathered sufficient knowledge from Ama Pava, our Mohalla birdshop owner, about feeding them. Songbirds; a variety of them thrushes, wagtails, pipits, golden oriole, tits, doves and parakeet in different types of cages, dome and pyramid-shaped kept me glued to his shop. I wished to have them all and fill our home with their merry songs that Pava told me were their mystic incantations- he also said to me that he caught these birds in and around Dal and Nageen lakes and Badamwari. If these were found in Baramulla, he did not know.

Staring on the Deed (gate) on Saturday evenings and enthusiastically waiting for my father became a hobby. His very entrance brought warmth and glow to my face- for me, he for me was no more a weekly visitor. Equally, the wish list of gifts for presenting to the father also multiplied. In class four, my elder brother, on occasions, travelled with his father to Baramulla and stayed there till the weekend. He was grandmother’s, ‘dear darling’, so it was now a double wait for her son and grandson, and my expectations for gifts also had doubled- terracotta and wooden toys.

Nevertheless, Saturdays, and Sundays, when my father would be around, were not only days when our house was abuzz; it used to be a whole week affair. Our house was very strategically located; it was less than two hundred yards from the Jamia Masjid and near the bus stand and tonga adda, from where people would go to Hazratbal. On Fridays, some of our relatives and friends of my uncle Ghulam Nabi after offering pa’shin namaz ( Duhur) at Hazratbal and the Jamia Masjid on their way to their homes, dropped at our home for chitchat, a smoke from Hubble-bubble, a few cups of Nuna-chai from sizzling and hissing Samovar and Chochwor. Our house was a stopover for my uncle’s friends from places as far away as Ram Bagh and Solina working at the Government Silk Factory – famous for the 1924 worker revolt against corruption and the discriminatory wage system instituted by the Dogras. From their homes, they cycled to Hazratbal for Juma prayers. A few – overflowing with devoutness – travelled miles on foot to say Juma Namaz at the Jamia Masjid. One of the prayer goers to the Jamia Masjid was a hugely turbaned, older person from Nalbandpora with impaired hearing. His name remained stamped on my mind for quite some time; it has now evaporated. However, the suffix of his name ‘Haji Sahib’ persists. After matriculation, my uncle worked part-time in his shop for six months and maintained his accounts. The two, however, had developed a quasi father and son relationship, which survived many tides of the times. Haji Sahib was perhaps the biggest bicycle vendor in the city and a great devotee of the exiled Mirwaiz Yousf Sahib. Deep-down, his craving for the return of Mirwaiz to Kashmir made the older man paddle his way to the Jamia Masjid in hot summers and even when the roads would be frozen to the glass. Neither the Hubble bubble nor the discussion about Sheikh Abdullah and Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad on the wooden platform interested him. His deafness would go, and adrenaline would run through his veins once the name of Mirwaiz Sahib was mentioned- it would also bring tears to his aged eyes. What intrigued my elder sibling and me was his antique cycle, fitted with a dynamo and carrier. He had purchased it from a junk shop in our Mohalla- famed for selling old goods of British Sahibs. I don’t remember having ever seen my father squatting on the wooden platform and chitchatting with the visitors, even after he had been transferred from Baramulla.

My father chose not to talk politics at home; he perhaps had no time for it. Or there was any other reason. On weekends at home, he had his schedule. His day in all seasons and weathers started much before the roosters’ call. One of his interests after saying his Fajar prayers in one of two Khanaqahs in our neighbourhood, one just hundred and fifty yards from our home and another on the Jhelum bank at ten minutes’ walk, was brooming the compound of the house and the lane connecting our house to the main street. Despite domestic workers, his sweeping activity was puzzling to the neighbours – it did not cause much concern to us, the children; perhaps we did not understand these social nuances and niceties.

Having made it to Baramulla, in his government accommodation- a hutment on the bank of river Jhelum, my father has had sleepless nights waiting for the first bus that would leave for Srinagar. There were stories on the family grapevine; on that fateful night that saw Srinagar plunged into darkness, he had reached from Mohra to Baramulla in the din of gunfire and rain of bullets. And when he was treading on his way to Baramulla, the Maharaja and his Rani had packed all their diamonds, gems, jewellery, brocades, and Persian carpets under gaslights. And in a caravan of motorcades and trucks, leaving the city without petrol they were chuckling on slushy Banihall cart road towards Jammu. I always was curious to know the whole story, but I was too young to have asked him.

I can’t tell if my father was not talking politics for fear of snoopers and eavesdroppers appointed by the Propaganda Department, headed by very tall and stout Stalinist from the West Punjab- more known to people for his British wife. I don’t have the faintest idea of seeing him glued to the radio after 8.30 PM when the main Urdu news bulletin was broadcast from Radio Pakistan, followed by BBC Urdu Service and All India Radio Urdu news. As we learned later, those were the days when radio sets could receive only selective radio waves. Listening to these night news bulletins had become an obsession and OCD for a big chunk of people- it had become a part of the downtown culture. The newsreaders with a golden voice like legendry Shakeel Ahmed – who people had heard from WW-II days, Anwar Behzad and Saeeda Bano kept them in thrall. Most of them were larger than life for all downtowners – ‘they relished surpy tongue’, as the Kashmiri adage goes. An eerie silence like those in the deeps woods was in the radio room for those forty-five minutes. Some with their eyes shut, as if in deep meditation, listened to the news, commentaries and analysis. Zafar Pyami Ki Tabsara, a report on the contemporary political scenario that followed the All India Radio Urdu News at 9.15 PM, was like a desert after a sumptuous dinner to all those sitting in the greenish-white clay daubed room of our house. Everyone, my uncle Ghulam Nabi, his friend Ghulam Qadir Bangari, and a couple of other daily visitors to our home believed that he was a Muslim from Lucknow or Delhi who wrote these Tabsara.

None of them thought that he was Dewan Beriender Nath, Binder as he was called in the family of B.P.L. Bedi, a left-leaning Hindu. The family had adopted Binder as their child. His commentaries on Kashmir from All India Radio had endeared him to many a serious listener. But, none knew his antecedents- as a student at Allahabad University, he was at the forefront of the ‘student’s communist movement’. And after a crackdown on this movement, he took shelter in Kashmir, where his mentor B.P.L. Bedi and Freda ruled the roost. Here in Srinagar, he stayed with the Bedi and was counted as a family member. And he got admission to the Jammu and Kashmir University, where he made many friends- this enabled him to know the nuances and fragility of Kashmir politics.

From childhood, his name was etched on my mind also. As late as 1980, my boss asked me to conduct a senior journalist and commentator Dewan Beriender Nath to Chief Minister Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah. But I was as ignorant about him as those sitting in the Radio Room of our home. I did not think in my wildest dreams that the guest sitting with me in the old Willie jeep was the famed news commentator Zafar Pyami. Despite knowing him as a member of the Bedi family, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah was hesitant to enter into a free and frank conversation with him and asked me to sit in the room during the conversation. However, I found him a fine suave and soft-spoken gentleman with no airs about himself. I became friendly with him, and he asked me to write a weekly column for his news agency, the ‘Press Asia International’. For a couple of years, I continued to write for his feature agency. Many vernacular papers in Punjab and Delhi often picked up my wite ups and published them prominently.

Back to my father’s story, he visited the radio room in the evening whenever he found time. And exchange pleasantries with some neighbours who, almost at every dusk, turned up at our home for listening news from Radio Pakistan and some popular programmes of Radio Azad Kashmir. Nonetheless, he never joined the discussions over smoke from a hookah. I don’t remember seeing him occasionally enjoying a smoke from the hubble-bubble, but he had a taste for top brand cigarettes, Triple Five and Gold Flake- but he never smoked at home. Interestingly despite being a native- a proud native with roots connecting him to the earliest settlers in the valley, I have never seen him draped in traditional pherans. To keep himself warm at home, he had a choice for raw Pashmina blanket popularly known as Pahamba Chaddar or its more refined cousin Dussa- then perhaps it cost between Rs. 200 to 300. Compared to him, his younger brother greatly admired pherans; the two brothers did not differ in costumes alone but temperament.

Saga of A Native Family

I sometimes wonder if my father would sit under the tso: ng, a cotton wick lamp fuelled by mustard oil that used to light homes during long wintry nights, listening to stories from his grandmother. Sadly, I never got a chance to ask him. Perhaps I was too young, or he was in a hurry to leave us early without saying goodbye. Nothing of his childhood ever leaked into the evening family gossip. But stories about his childhood pastime, youth hobbies were scattered in the attic of our house- ‘my wonderland.’ The storybooks like Jung Nama, Alif Laila, Rustum Sohrab, and Gulraiz with garish sketches on their covers and old novels stuffed in one of the Sandals immensely testified his love for beautiful and powerful stories during his childhood and boyhood. The booklets on Kashmiri Sufiana Mausiqi and its different Maqams and old gramophone record player, bunch black discs some broken and a few intact did tell he had been music lover perhaps a connoisseur.

Whether he had heard stories from his grandmother or not. But I could imagine, he defiantly would have heard stories in chaste and mellifluous Kashmir from his mother Khayr Ded- my grandmother. I don’t know if my grandmother real name was Khadija, or it had been shortened or distorted to Khayr Ded as was in vogue those days. However, the Khayr Ded name sounded excellent and meaningful like many other Kashmiri names adopted by native Muslim women. What made me believe that my father might have heard some grand stories, of course with a moral from my grandmother, after all in her seventies for me, she was the most extraordinary storyteller? More eloquent and fluent than the ‘Sazandars (barads) that often visited Ramzan Khan’s Mandi (timber depot) adjacent to our home in the wee morning hours and put ballads of Rustum and Sohrab, love lore of Laila Majnu and Heemal and Nagari to music.

In Ded’s quiver of stories, our no ancestors had made it from the dusty plains of India along the banks of Ganges to the land of lakes and peaks. In our family basket, there were no stories of our forefathers having climbed over the rugged mountains of Afghanistan or crisscrossed the vast deserts of Arabia to land in the lap of mountains and high peaks. The only story in the family bin was that we were natives who tended a smallholding; somewhere on the Srinagar-Baramulla road. And in one of the devastating floods some three centuries back, it had been washed away, and the humble house crumbled with all belongings carried away by the gushing waters. To eke out a living, the pauper family had made it to the city. Instead of living a parasite’s life, like a drone shifting from flower to flower, they had moved from one blue-collar job to another. Almost living the gypsy life, they had changed three homes before making it to the house around the Jamia Masjid where my father and I were born and adopting it as their permanent abode. The date and year of the new dwelling could be found in the stamp papers of Dogra Durbar, lying in the iron safe fixed in the wall of a room. But, it never caught my imagination, even during my youth, to know exactly when the house I was born was built. My grandmother once told me that she, as a bride, had walked from her father’s house into the three-story home of burnt bricks constructed by my grandfather during the times of Old Maharaja. It perhaps could be at the turn of the nineteenth century because, in 1963, she passed away at eighty. The family could trace its genealogy to three generations only before my father, Sadiq Joo, my grandfather, Aziz Joo, his father and Ahad Joo, his grandfather. None in the family precisely knew when it had graduated to Islam. However, the general impression was it had happened in the fourteenth century when Mir Muhammad Hamadani, the illustrious son of Mir Syed Hamadani, was moving around the valley with missionary zeal. What religious beliefs our ancestors did follow before adopting Islam as their way of life would only be a surmise. The family might have passed through many vicissitudes, lived through more challenging times and cherished many beliefs and faiths. Living near nature might have shaped their worldview about religious beliefs and moulded their character. If they followed Mahayana doctrine at any point in time will be wild guessing. Of course, at the time of coming within the fold of Islam, the family might have been part of the broader spectrum of religious beliefs in fashion.

Nevertheless, I have vivid impressions that the family followed the Naqshbandiyah Sufi order. The legacy passed on to the family from my grandfather’s times was in the family narrative. For this native family esteeming Naqshbandiyah order ostensibly, there could be no reason other than living near four-hundred-year-old Khanaqah Naqshbandiyah (1633 AD)- an abode of peace, tranquillity and spirituality. On the third of every month of the Hijra calendar, a samovar of Kehwa and basket full of bread was carried to the Khanaqah- my elder sibling and I might have done this errand job dozens of times. On this day, devotees collected for Khatamat – special prayers in the Khanaqah. On many other occasions, a big majama copper plate filled with halwa was taken as an offering to the Astana on the premises. Every year on the 3rd of Rabiʽ al-Awwal, the Urs of Naqshband Sahib was observed with solemnity, friends and relatives were invited to a multi-cuisine lunch or dinner. The tradition continued as late as the eighties of the past century till the family was fragmented and shifted to various other localities. Both my father and uncle were proficient enough in Persian and Arabic; they remembered scores of naat and manqabat as the adage goes by heart.

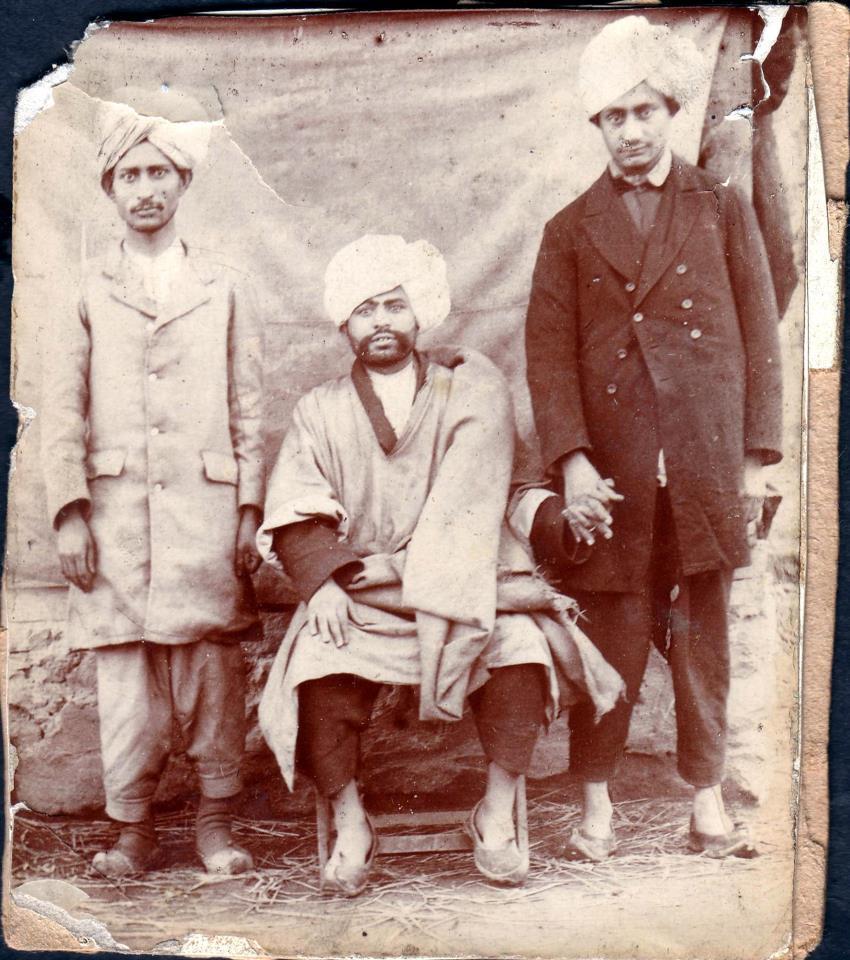

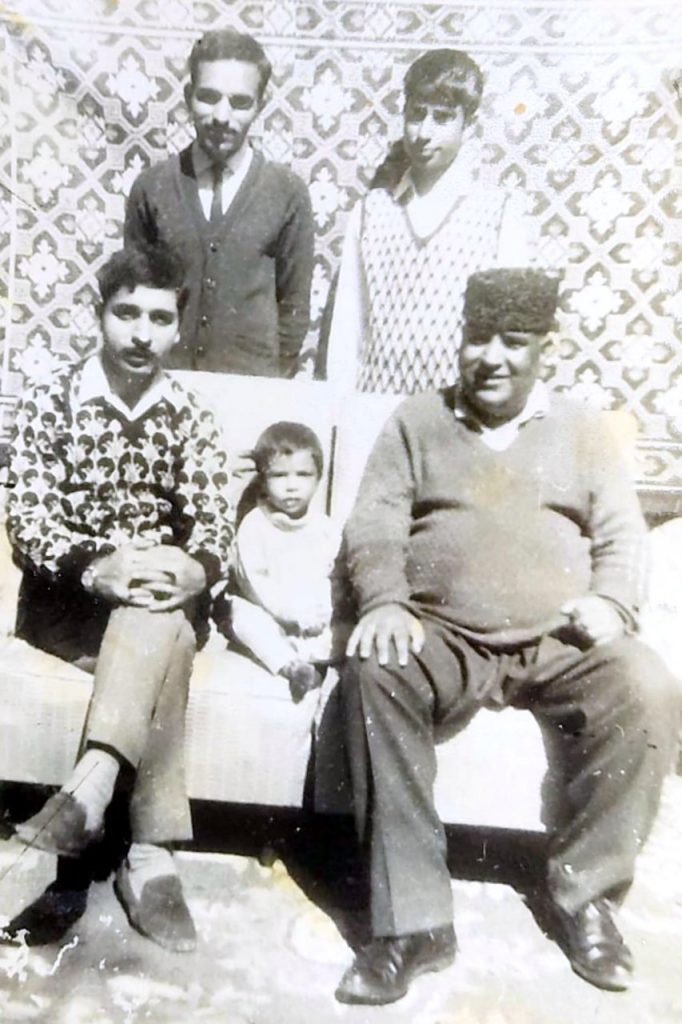

In far as contours of face my father, he resembled his mother as my uncle resembled his father. Like his mother, my father was lean and tall, with a typical hooked Aryan nose five feet and ten inches in height and my uncle round-faced, quite stout five feet six to seven inches in height like his father. I was also curious to know how my dad looked in his childhood; as I started getting attracted more towards my father after he ceased being a Saturday visitor, my curiosity to know how he looked as a child intensified. Perhaps making a family album during my father’s childhood was not popular in our class of people; it might have been fashionable ‘ with the aristocracy.’ Someone has said, ‘dads are always heroes of their sons-‘that may not always be true, but the truth is that every child imagines how his father looked at his age if he was his mirror image or not, and they looked into old family photo albums. There were no albums in the sandooks in the loft or on shelves. Still, some group family pictures in frames pegged to the greenish clay daubed walls, feasted at by silverfishes on corners, provided a window to know about costumes and jewellery in the fashion in the recent. A large family picture in a paper mache frame was hanging from a wooden peg on one of the walls. The frame perhaps had been made by Aka Malik, the patriarch of Malik family, the only Shia neighbours we shared Pa’chi baharun with- the wooden planks compound partition. Mohammad Malik, another scion of the family and his wife and three sons lived in our neighbourhood during my early childhood. I have fond memories of Sa’ka (perhaps Sakina), wife of Mohammad Malik- she was pretty elderly, brimming with love and affection. Some ace photographer had taken the photo with the vintage wooden camera on a tripod under a dark cloth cape. These wooden cameras outside many photographers shops in Basant Bagh and Gow Kadal areas had a great attraction for me during my school days. These were used as late as our days at the university campus to take the class photographs. In the 12/15 Inches, family picture pegged on the wall probably shot in autumn of 1930, when my father was eight or nine years old, I have seen him wearing a fez cap and a three-button coat touching his knee caps a crumpled trouser standing on one side of the photograph. Men were sitting on a wooden bench. Those in the picture were Sidiq Joo and Ramzan Joo, my grandfathers from father’s and mother’s side and their brother Habib Joo. And there was one Qadir Kak, who was not a member of the family but had been brought up by the family. There were a lot of stories about Qadir Kak’s tomfooleries and cowardice in the family tales. Out of many of his pranks, one often found a mention:

Whenever the royal procession passed through the street of our locality on its way to temples on the foothills of Koh-i-Maran (Hari Parbat), people needed to raise the slogan “Maharaja Bhaduar Ki Jai.” Instead of Jai, Qadir Kak had cried Kai (vomiting). The horse-mounted soldier (ra’sali) had chased him through the lanes of our Mohalla, and he had taken shelter in huge earthenware granary and out of fear, he had pissed inside’.

All women in the picture were dressed like other native women; long pherans were touching their knees, the headgear adorned with lots of silver pins- some with tiny turquoise tops. My father might have graduated to a suit from his three-button coat after finished his education and joined the Maharaja’s Government. However, I always saw him wearing a well-ironed suit, an astrakhan cap and Ambassador Shoes.

PART FOUR

Mothers are a massive influence on children; it may sound a cliché, a trite, but it is as good truth as the sun rises in the east. ‘They are the bones of the spine, as someone has said that keeps children straight and true. The way my father was, his disposition and demeanour did tell he was his mother’s child. She was a wonderful human being, her supplications like her store of stories never exhausted. Sitting long hours on Namaz-i-Raad, soft and spongy prayer mat made out of dried weeds, she, without holding her breath, endlessly prayed for neighbours children, particularly girls and her children and their progeny. Often her duas ended with supplication: ‘kuli a:lmɨken ɡulan sa:n mya:nen ɡulan ti kʰǝ:r’ [1] (May Allah’s blessings be on all children of the world including my own!)

I am amazed how this old unlettered woman, ‘love-for-all incarnate, had understood the very essence of altruism. The marriage of all daughters in the neighbourhood always haunted her- it was one of her significant concerns when supplicating the Almighty. She eagerly waited for good news about marriages in Kha’ji Ma’si (Khatija) ‘s family most of the time. In her joint family, there were six unwed daughters of marriageable age. She was grandmother’s best friend and companion to the Jamia Masjid at Zuhur and Asar prayers. Her wait for good tidings about the marriage of neighbours daughters was unending; nonetheless, the Saturday after-dusk wait for her son returning from Baramulla was now about to end. For ten years long years, she had perpetually gazed at the main door of our home on the weekends for him. It was very much in the air at home to the delight of everyone that Thakur Baldev Singh, my father’s boss, had recommended his transfer to Srinagar. The state was going to venture into the most extensive tourism show- the Jashin-I-Kashmir and my father’s services were requisitioned in that regard, as were those of many other cogs of the administration. These state-sponsored festivities would also have much fun in stock for children; neither my siblings nor I knew it. There was nothing big for me in the news about the father’s permanent positing at Srinagar. It did not bring any warmth to my cheeks but a frown. I understood Amir Khan would be no more accompanying him with gifts for children. I also believed my dream of having a sanctuary of birds like that of Ama Pava was dashed. Now no birds will come from Baramulla.

My heart was ballooning with protests, but my discords were of no avail. One fine evening, a Tonga stopped on the street outside our home with all personal belonging of my father. Amir Khan brought them one by one inside our house. Seeing a big metal trunk as part of the luggage, I started imagining toys inside it. But not finding a pyramid-shaped cage with thrush or dove as part of the baggage saddened me. But, one thing that father had not forgotten was bringing a giant rooster and Shikar, a Pechin (flying duck) for the family. Once a bustling town, Baramulla had almost turned into a sleepy village. The ‘road’s closure’ had taken a toll economy of this significant city gateway to Srinagar. For centuries the township on the banks of Jhelum had welcomed travellers from Central Asia and the West. ‘There were no toy shops; even the traditional wooden and terracotta toys had disappeared from the markets. The father regretted it, but it did not console me.

Now, I was not a tot of kindergarten but a third primary boy of Islamia High School, also my father’s alma mater– an institution that always made him proud. My daily routine, too, had changed; the Watanigour days when mother lullabied me to sleep for long hours were over. The crib was back in the loft, waiting to rock the future babies of the family. Then there were no beds for children in our home, sleeping on the floor; three of us, my elder and younger sibling, and I shared a long and heavy cotton quilt. Much before mother or father would prompt us to come out of bed, it was old Cheri Gor and his son from a Cherigari Mohalla, whistling the goats and ewes and bells jingling in their necks who woke us up and made us throw away the quilts and ready ourselves for going to school on the dot. Those boys not making it on time to the school had to suffer a cane charge on the gate and at the morning assembly. The father’s permanent presence at home had made a difference; drinking goat or ewes’ milk had become almost as enforced as washing face before entering the kitchen. The goat’s and ewe’ milk sharpened one’s intelligence; everyone in the family believed in this age-old dictum. Mahida Hakim of the locality had strengthened it after he had told our grandmother to feed ewe’s or goat’s milk to children to improve their immunity against cold, cough and other diseases. Our father wanted to see us mentally wise and physically stout. Like many others, he too looked at ewes milk as a potion. He paid Ama Cheri Gor in advance to ensure he stopped at our door with his flocks for dispensing fresh milk without breaks.

Despite being a man with few words, father occasionally engaged in conversation with the Cheri Gor, who looked to us a shepherd from the Nazareth with his head covered with a blanket. [2] He would make all inquiries from him about his flock and income if it sufficed him and his children were going to school. To pay attention to the have-nots was perhaps innate to his temperant. He would talk at length to Mohammad Shaban Sheikh, who would broom the premises of Khanaqah -I-Naqshbandiyah before the birds started chirping. He shared jokes and chuckled with Jala Band, the shoe mender and shoe polisher who visited our house every morning to collect shoes for polishing. He lived just at three minutes’ walk from our home in an evacuees’ house. It was reasonably a good house with ornate windows and a big doorway. Everyone knew that the owner in 1947 had migrated to Lahore, but nothing was precisely known how Jala Band, his wife and their adopted daughter had occupied the house? A formerly Hafiza owned the home for decades, and Jala Band’s wife was either her relation or her adopted daughter, all that was part of Mohalla gossip. Some others would say Jala Band was her adopted son. Jala Band had sub-let top floor of the three-story house to Tangewala brothers Jamal and Nunda, notorious cannabis smokers, but they owned the best stallions; all bridegroom dreamed of riding on to brides houses.

Much before, we would toss aside our comforter to watch Cheri Gor milking goats and ewes father would be back from his pre-dawn religious obligations. He was an early riser, and he religiously followed his schedule. He never deviated from his plan comparable to the needles of an old wall clock that struck every hour. He got up in wee morning hours before Muzzein Subhan Sonur, at his highest pitch, gave Azan from the Mohalla Masjid or the bell in the minaret of the Jamia Masjid started ringing. On most of the days, he walked up to Khanaqah-e-Moula, a fourteenth-century hospice on the bank of Jhelum, to say his Fajar prayers- and as a routine visited his orphaned niece married near Zana Kadal. Her house had been gutted in a devasting fire. At home, he would be busy as a bee in reading the holy Quran; rarely have I seen him reading it louder in the family in Kitchen-cum-Sitting room. And by the time we finished our breakfast- comprising naun chai and Tchout, dressed up to the nines, he would be ready to leave for the office. Sometimes, he would hire a tonga to his office and during Jashin Kashmir days and other occasions, a jeep would honk outside our home to carry him to the office. For my siblings and me, the name of the driver of the jeep was Phahpa, perhaps a nickname for his stammering, and none of us ever tried to know his real name. During the Jashin-I- Kashmir days, which included programs like Shab-I-Shalimar and special musical concerts and late-night shows at the exhibition grounds, he returned late to home, many a time we would have gone to bed.

Our father was not didactic; he did not prescribe a list of dos and don’ts to us, but there was a lesson in all his actions for putting us on a solid pedestal for enabling us to lead a life of Iqbal’s Shaheen’s and perfecting our lives. In the morning, when Jala Band brought back shoes after polishing them, father, before wearing his boots, checked not only toes but if the heel caps and top-line were as sparkling as the toes. He would even see if the shoes’ welt and heel were shining as bright as the toe. If the heel caps would not be, he would quickly rub them with a duster. Sometimes, he would ask my elder sibling and me to polish his and our shoes. My elder brother, who was three classes ahead of me, had perfected the art of polishing. He evenly mixed boot polish and cream and applied it on the toes and back of the shoes and, like a professional, rubbed the shoe with a piece of cloth and made them sparkle. This experience became a habit for him. Every Sunday, he washed his bicycle like a car washer with rubber pipe fitted with a jet and removed every bit of dirt from mudguards and made rims, spokes and hub gleam. His bicycle for its shimmer and add-ons bells, horn, dynamo and basket for books was comparable to a bride in traditional costumes and jewellery. His cleanliness and dress sense made him distinct from his friends. Despite my father’s efforts to make me a perfectionist, to my annoyance, he checked if I had polished the heel side of my shoes and asking me to redo it till it sparkled; I could not match my elder brother.

Procrastination is the thief of time’, believing in this golden line father did everything on time; in fact, punctuality was his second nature. I don’t remember a single occasion when he would be seen rushing against the time. He never grumbled over a missing hankie or his pen or misplaced wallet at the time of leaving for office- well in advance, he checked all his items. On the regular days, he would go to the office at 9 A.M. dot, and on much other time as his office engagements demanded, he left for office much early without any fuss. By the time he would depart for office, we got ready for the school. He ensured that we went to school in uniform as immaculate as his suits stitched by Dar Sons Tailors- a famed tailoring shop at Koker Bazar, Amira Kadal. The most fashionable material for making uniforms was poplin and gabardine, a durable and lustrous cloth, sadly quick to get wrinkles. Terylene and terry cot fabric might have been discovered. But, the new material was yet to take over the cloth markets and make people crazy about it. Our father ensured we wore starched uniforms – sky blue poplin shirt and khaki gabardine trousers as tidy as the olive green soldiers who often strut on the streets in our part of the city. Instead of two uniforms, father got us at least four sets of uniforms stitched from a tailor living in a rented house near Ranga Hamam. He was not a native. Like another occupant, Kala Miss, he was also a christen. Kala Miss’ real name was Mrs William; she came to Kashmir in 1931, left in 1965 and died in Delhi in 1970. Having four uniforms was quite good for remaining tidy. My brother and I were never reprimanded, never cane-charged at morning Assembly like other boys in shabby uniforms.

Despite the father remaining busy and returning home very late, his presence at home instilled discipline in us in every respect. Instead of Sundays, our school remained closed for Fridays for its weekly holidays. On many Friday evenings, trips were arranged for us for enjoying the illuminations at Shalimar, exhibition grounds and other Moghul Garden in connection with the Jashan-i-Kashmir. Strolling across the Shalimar with father when it was inundated with lights of all shades and colours had its romance and beauty. It is was an experience that would wax an ordinary man lyrical. (to be continued)

[1] Thanks to Prof. Aslam for phonetics of this Kashmiri supplication.

[2]For details suggested reading “Ewes Milk and Brain Power”, Srinagar My City My Dreamland pp 88-90

Filed under: Editor's Take, Memeiors · Tags: Downtown Boy Srinagar, Father's Story, ZGM