Peace Watch » Book Reviews, Kashmir-Talk » Myean Kath – Life Writing Of An Educationist.

Myean Kath – Life Writing Of An Educationist.

Everyone has a tale to tell and a nostalgia to share. Nostalgia is cathartic but equally a life-writing that goes beyond biography. It not only ‘encompasses everything from the complete life to day-in-the-life, from the fictional to factional’ and connects us with others and their immediate past, social and cultural moorings. Some days back, a doctoral thesis by one of our young United States-based scholars Hafsa Kanjwal, Assistant Professor of History’ the University of Michigan, guided me to reading a life-writing ‘Chilman-se-Chaman,’ by Prof Shamla Mufti. This name has been part of the collective memory of a whole generation of girl students.

Myean Kath (Kashmiri) Chilman-se-Chaman (Urdu) is a blend of protest against an archaic social system, struggle of young women against patriarchal eccentricities, memories, and nostalgia. On filliping through the pages of this writing, I instantaneously established a bond with it. The book enabled me to establish a relationship with the author’s times and the social and cultural ethos of the author’s family. Taking me down the memory lane connected me to my teachers, school days, and days at the campus. The Father of the author, Saad-u-Din Chisti, was my theology teacher in class seven. Her husband, Mufti Ghulam Din, and her brother-in-law, Master Salam-u-Dinwere Principal and Headmaster of the two schools I was educated in. Mohammad Amin Chisti, a noble and humble man, was registrar of Kashmir University during my student activism days on the campus. One of the nieces of the author was my contemporary at post-graduation level. Moreover, it provided me a slit with a telescopic lens to peep into the social structures, customs, traditions, values, practices, and institutions of my father’s and grandfather’s times. Filliping through the pages of this beautiful memoir written in chaste Urdu, on umpteen occasions for my kinship with the downtown ethos and culture, I felt I was going through a compilation of the nostalgia, my column.

The first chapter of the book ‘Chisti Kocha,’ Sona Masjid, the lane author was born and brought up mirrors the social scene as obtained during her childhood in the twenties of the past century. The house of the author was on the banks of Kuti-Kul, a tributary of the Jhelum river. The rivulet, for the Maharaja’s soldiers drowning to death twenty-nine Muslim artisans in 1865, for raising their voices against the brutal taxes is part of our sacred history and popular narrative. Taking us to the historical past of the area she tells us that in the family manuscripts, nikahnamas and other documents of the family the area is mentioned as Bagh-e-Yousef- the palace of the last sovereign king of Yusuf Shah Chak is believed to have been in this garden. The rivulet gushed with translucent waters for the whole year. She also takes us on tour in and around her birth burg and introduces us to gardens lie the ‘Headow garden.’ These gardens had disappeared years before I was born.

Though nostalgic in tone and tenor, the author in this chapters intimately looks at the life of the boat women and women from the elite time. Those days drinking water tapes at homes were a rarity. In summers women, when everything around drowned in pitch darkness, went for a few quick dips in the rivulet. Young girls would do some swimming also. ‘The only pastime for the elderly women were visiting the Jamia Masjid on Friday to listen to sermons delivered by Mirwaiz Molvi Yusuf Shah mostly bordering on seeking penance and forgiveness from Allah instead of on knowledge and research. In writing , a yard of cloth cost two and half-anna, and it cost seven annas for making a male-trouser, but many could not afford to make a touser, author of Chilmen-se-Chaman gives us a vivid picture of economic deprivation of the Muslims of Kashmir during the Dogra rule.

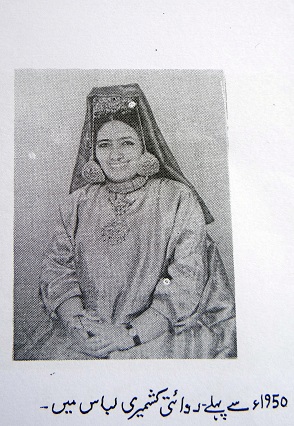

There are subtle protests of the author against the class distinction in the Muslim society that existed between natives and immigrants- that had arrived from Central Asia. She also tells us how a dress code such as two types of headgears’ Kasabas’ had been evolved to differentiated natives from the descendants of the saints from Central Asia. Quoting Prof. Shams-u-Din Ahmad, She writes ‘Kasaba’ had come to Kashmir from Central Asia- and there it was worn by one and all.

Making a mention of her teachers, Shamala Mufti tells us that her English teacher was Miss Birjees Mirajudin, she always insisted her students to read books outside their syllabi. She is remembered in history as Birjees Gani Rentoo, who was arrested by Sheikh Abdullah and sent to a jail in Jammu for presenting a memorandum to UNCIP team in 1948 at Srinagar and then exiled to Pakistan.

Shamala Mufti’s nostalgia is our socio-cultural history.

Filed under: Book Reviews, Kashmir-Talk