Peace Watch » Featured, Perspectives » In Defence of M.A. Jinnah

In Defence of M.A. Jinnah

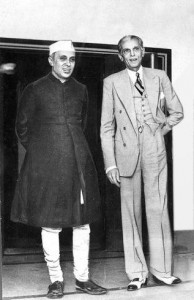

Mountbatten, Jinnah and Nehru

M. YUSUF BUCH

To hold Jinnah “solely responsible” for the Kashmir dispute is, of course, sheer calumny but sentiment and ethics apart, it is also a  breathtakingly grotesque contention. From the whole tangle of personalities, Indian, Pakistani or Kashmiri involved in the origination and hardening of the dispute either by commission or by omission, it foists blame on the one whose role was least indictable, indeed most honorable and based on perspicuous judgment. The two fateful factors that limited it and prevented it from achieving the results it could have done were his unfortunately growing ill-health and the disjointed character of the state of Pakistan in !947-48. I have not read the book under discussion but the words “Mountbatten presenting him (Jinnah) a written document in November 1947 on holding of plebiscite in Kashmir ” (I quote from Greater Kashmir) escort one straight to the region of unreality. Where and how did that document dissolve into thin air? How come Mountbatten, no friend of Jinnah, never mentioned it himself? Such documents are assertively referred to as the phenomenon of their rejection forms a major plank of the relevant argument in behalf of the opposite party; is it credible that India would not have played it up and blazoned it as mark of Pakistan’s negativity but, instead, maintained a discreet silence? Then again, in November 1947, Mountbatten was in no position to take any initiative, frame any proposals or make any offers on India’s behalf; his advisory role, facilitated by his cordiality with the Congress leaders, was limited to striking an occasional cautionary note and smoothing India’s path with the princely states which were not subject to dispute with Pakistan. After the transfer of power, the framers of policy were Nehru and Patel as formatively influenced by Gandhi. If they had contemplated the course of action indicated in the mythical document, they could have formulated it themselves not in convoluted language but in plain terms and, without any unneeded emissary, conveyed it challengingly to Pakistan.

breathtakingly grotesque contention. From the whole tangle of personalities, Indian, Pakistani or Kashmiri involved in the origination and hardening of the dispute either by commission or by omission, it foists blame on the one whose role was least indictable, indeed most honorable and based on perspicuous judgment. The two fateful factors that limited it and prevented it from achieving the results it could have done were his unfortunately growing ill-health and the disjointed character of the state of Pakistan in !947-48. I have not read the book under discussion but the words “Mountbatten presenting him (Jinnah) a written document in November 1947 on holding of plebiscite in Kashmir ” (I quote from Greater Kashmir) escort one straight to the region of unreality. Where and how did that document dissolve into thin air? How come Mountbatten, no friend of Jinnah, never mentioned it himself? Such documents are assertively referred to as the phenomenon of their rejection forms a major plank of the relevant argument in behalf of the opposite party; is it credible that India would not have played it up and blazoned it as mark of Pakistan’s negativity but, instead, maintained a discreet silence? Then again, in November 1947, Mountbatten was in no position to take any initiative, frame any proposals or make any offers on India’s behalf; his advisory role, facilitated by his cordiality with the Congress leaders, was limited to striking an occasional cautionary note and smoothing India’s path with the princely states which were not subject to dispute with Pakistan. After the transfer of power, the framers of policy were Nehru and Patel as formatively influenced by Gandhi. If they had contemplated the course of action indicated in the mythical document, they could have formulated it themselves not in convoluted language but in plain terms and, without any unneeded emissary, conveyed it challengingly to Pakistan.  This would have easily made its rejection an untenable position for anyone on the Pakistan side, including even Jinnah. But they did nothing of the kind. Then again, the laughable allegation of plebiscite having been rejected by Jinnah in November 1947 is destroyed by the abundantly recorded fact of the stand Pakistan took in January 1948 at the United Nations. That stand would not have taken shape if it lacked not only Jinnah’s formal approval but also his active support and endorsement. The proposition of a fair and impartial plebiscite under the auspices of the United Nations was the main thrust of that stand.

This would have easily made its rejection an untenable position for anyone on the Pakistan side, including even Jinnah. But they did nothing of the kind. Then again, the laughable allegation of plebiscite having been rejected by Jinnah in November 1947 is destroyed by the abundantly recorded fact of the stand Pakistan took in January 1948 at the United Nations. That stand would not have taken shape if it lacked not only Jinnah’s formal approval but also his active support and endorsement. The proposition of a fair and impartial plebiscite under the auspices of the United Nations was the main thrust of that stand.

A point needs to be stressed here which may superficially appear as a nuance but is actually a matter of fundamental importance. The term “plebiscite” without any defining characteristics can be dangerously deceptive. There is as much opposition between plebiscite held under the coercion or intimidation of a heavily militarized partisan regime and subject to rigging and manipulation, on the one side, and plebiscite administered by an authority like the United Nations, on the other, as there is between plebiscite and its complete negation. If anyone representing Pakistan or Kashmir would accept the proposition of a plebiscite without the safeguard of its impartial auspices, there would be ample ground to impugn his integrity or even doubt his sanity. This remains true as much today as it would have done at any point since the inception of the dispute. Jinnah would always have been the very last person to fall into the kind of trap which would have stultified Pakistan’s stand and doomed Kashmir’s future.

At the United Nations in 1948, India felt it most inexpedient not to make a show of accepting the proposition of an impartial plebiscite under the United Nations auspices. But India’s real intentions were exposed only some months later when she turned down the so-called truce proposals which were made by none other than the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan and were meant to help effectuate the plebiscite. There is nothing on record which would even faintly suggest that, at any point of time, Indian leaders became reconciled to the prospect of India losing Kashmir or, far less, fearful of the possibility of being defeated in Hyderabad and as a result made any constructive offers which would have settled the Kashmir dispute. All contrary readings are moonshine.

At the United Nations in 1948, India felt it most inexpedient not to make a show of accepting the proposition of an impartial plebiscite under the United Nations auspices. But India’s real intentions were exposed only some months later when she turned down the so-called truce proposals which were made by none other than the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan and were meant to help effectuate the plebiscite. There is nothing on record which would even faintly suggest that, at any point of time, Indian leaders became reconciled to the prospect of India losing Kashmir or, far less, fearful of the possibility of being defeated in Hyderabad and as a result made any constructive offers which would have settled the Kashmir dispute. All contrary readings are moonshine.

As I say this, I do not in the slightest degree imply that the project of Kashmir’s liberation was hopeless at any historical point or has so become now . All I mean to suggest is that we must extricate the narrative from imaginings and shadowy perceptions and not let ill-informed or irresponsible historians—there have been plenty in the case of Kashmir—distort the record or depress our outlook. A prime requirement is to avoid the grave historical fallacy of treating the Kashmir story as a whodunit. Doing so exposes it to the atrocity of concoctions in history’s guise. Judging from your summary of the central point in it, the book under discussion is a telling example. To personalize a phenomenon of multiple causation is to falsify history.

If I were to counsel historians or commentators emerging from our younger generation, my emphasis would rest on a dual point: first, the importance of not encouraging sensation-mongering or the desire to show off or sheer irresponsibility to falsely oversimplify a problem or episode or theme or experience as shrouded in complexity as Kashmir; second: equally vital, the imperative of not making the account unrecognisably dry and washing away all human elements in it that evoke well-merited castigation or praise.

As far as complexity is concerned, I would cite as an example one simple event: the tribal incursion into Kashmir in October 1947. From the viewpoint of Kashmir’s freedom, was it good or bad? Three of its conseqences were unquestionably harmful: (a) it emboldened the Maharaja to do overtly what he had been plotting for months i.e.formally offering accession to India; (b) unwittingly it lent some credibility in the eyes of the Kashmiri masses to Abdullah’s nationalistic posture; it thus had the effect of encouraging the personal ambitions which swayed him and blinded him to Kashmir’s fundamental and enduring interests; (c) it presented a false and unattractive picture of Pakistan–at that time a new-born state– to all who were not well-informed— which means all and sundry except a few. However, looked at from an opposite perspective, the event had an immediate result which justifies eternal thanksgiving; it averted the genocide of the Muslims of Muzafferabad and environs which was an important item in the Maharaja’s military strategy and would have definitely occurred had the invasion not taken place. So, what verdict can one invite, if one is seeking truth and justice? Alas, except in rare historical contingencies, neither of these desired objects presents itself in simple dress. The best one can reach is a qualified judgment.

As one separates the different factors, both indigenous and external, whose interplay shaped Kashmir’s

fate at perhaps its most critical point, one can identify the following:

a) The unshakable determination of the Congress leadership, particularly the Gandhi-Nehru-Patel triumvirate, to demonstrate their rejection of the concept of Pakistan( the so-called two-nation theory) as distinguished from their pragmatic acceptance of the two-state solution which brought about the emergence of Pakistan. To their minds, the latter seemed unavoidable for the purpose of compelling the exit of the British but it could be reversed at an opportune time in future while the incorporation of Kashmir into India would be a permanent gain. Kashmir as part of India would remain a standing refutation of the raison d’etre of Pakistan.

b) The role of Hari Singh, the Maharaja. The fact that he did not offer accession to India immediately or reasonably soon after its establishment has been taken by some British and other historians as a sign of indecision on his part. The supposition is baseless. He would have preferred death over acceptance of Pakistan’s sovereignty. Though firmly determined to accede to India, he wished to do so when, with an opportune shifting of weight in the Indian cabinet between Nehru and Patel in the administrative context of Kashmir, he would secure satisfactory terms, perhaps some kind of quasi-independence for himself and his successors. Whatever fears and doubts he and his Dogra counsellors initially harboured were decisively removed by two events: one, on just the eve of the partition of British India, he had to respond to Gandhi’s unmistakable warning to dismiss his Kashmiri Pandit Chief Minister who seemed to be capable of steering the ship in a direction not exactly to India’s liking; two, in late August 1947 he ordered Shaikh Abdullah’ release from imprisonment and at a meeting with him in the palace arranged for the purpose, he felt amply reassured about the navigability of the policy of not acceding to Pakistan.

c) The wholly disingenuous role of Shaikh Abdullah and all those colleagues of his whom he coaxed or bullied into submission. This requires detailed analysis and it takes the narrative back to 1946 when Abdullah rejected Jinnah’s most generous proposals for the formation of a united organization of Kashmiri Muslims. His effort to recapture his erstwhile popularity with the Kashmiri masses, unmatched in Kashmir’s annals, by launching the “Quit Kashmir” movement under the guidance of a few Hindu intellectuals from Punjab had not taken long to peter out. It was because of his own perversity that he could find no shelter except under India’s umbrella. This should not bring into question the fact that turnabouts constituted his favourite modus operandi; later on, he spent time under Pakistan’s patronage with no clear aim except his personal welfare.

d) The parlous nature of Kashmiri leadership, especially the lamentable disunity between the Muslim Conference and the National Conference. If this had not existed, Kashmir’s history would have been different altogether.

e) The disparity between the two states of India and Pakistan in all respects except formal and legal sovereignty: one was a fully-fledged state while the other was not yet in full control of the apparatus of governance—in other words, India was a cohesive organization while Pakistan was only “a work in progress” That the Pakistan Army was not yet even a compact entity explains why Jinnah’s characteristically straightforward directive to counteract India’s move of marching into Kashmir had to be withdrawn at the request of Pakistan’s own cabinet. This had far-reaching consequences, none to Kashmir’s or even Pakistan’s benefit.

f) The typical bickerings among Muslim notables who, if free from dissensions,could have played a consequential role. In the case of Kashmir, the tribal raid took place in a welter of jealousies which made its aftermath so unimpressive as to raise the question whether, for the cause of Kashmir’s liberation, it signified an advance or a retreat.

(Author is former Advisor to Secretary General of United Nations. This piece is exclusively written for GK)

Filed under: Featured, Perspectives · Tags: Jinnah, M. Yusuf Buch, muhammad Ali Jinnah

Comments are free.